J'accuse! Better yet, je sue!

One sure sign of weakness is responding to criticism with lawsuits. I'm not sure what freedom-of-speech guarantees exist in Japan, but this suit against the governor of Tokyo has to fail. Governor Shintaro Ishihara is being hauled into court by a group of French teachers and translators for making two simple points about their beloved tongue. His first point was that French is a "failed international language." Well, this is debatable, but it does appear that English is eclipsing French as the world's lingua franca.

Ishihara

Actually, the "franca" in the phrase lingua franca means Europeans in general, not the French (medieval Arabs referred to all Europeans as "Franks," and the Franks spoke German, anyway). The "Frankish language" to which the phrase refers was a sort of pidgin spoken by traders in Mediterranean ports, more Italian than French, and borrowing from Greek, Arabic, and Spanish as well. It fell out of use in the nineteenth century, though bits and pieces made their way into Polari, a mid-twentieth-century gay slang (those macho dockworkers ... who would've thought?). Today the term lingua franca more commonly refers to a language used to facilitate communication among speakers of different languages, as at the U.N. or the E.U.

French remains the most widely used common language of the U.N., but since the accession of ten new nations into the E.U. last year, English has superseded French in the hallways of Brussels. Technically, the E.U. has no official language, and all meetings, proposals, drafts, minutes, etc. must be interpreted and translated into all of the twenty currently recognized official E.U. languages, including Maltese, at a cost of half a billion euros per year. There have been proposals to streamline communications by adopting an official, "working" language, but that might offend the Maltese, so we can expect bureaucratic inefficiency to persist.

Calling French a "failed" international language is extreme, or at least premature. Despite the rise of English, French is undoubtedly the language that diplomats from most of Africa and much of southeast Asia and the middle east use when conversing with Europeans. It's still in U.S. passports alongside English, though it has been demoted somewhat by the recent addition of Spanish. To see true failure as an international language, look at Esperanto. Incredibly, the U.N. persists in wasting money on what never should have been more than an award-winning science-fair project. Esperanto turned out to be more of an exercise in creating a new dead language--another linguistic cause for fanatics to desperately attempt to keep afloat through newsletters, vanity-press publishing, and hotel conferences. Dockworkers and circus performers in Marseille, Tripoli, and Genoa proved better at creating an international language than the United Nations. Perhaps we should create a special seat on the Security Council for them, or put them in charge of peacekeeping operations.

So what exactly is Ishihara's beef with the most romantic of the Romance languages? Well, his second point is better reasoned than the first: You just can't count on the French. Oops, I mean you can't count in French. Not clearly, anyway.

Arrgh.

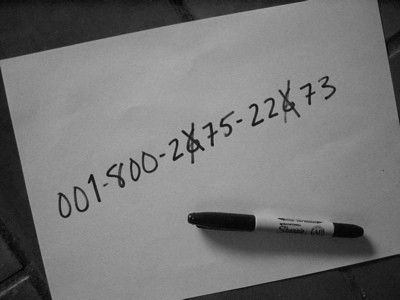

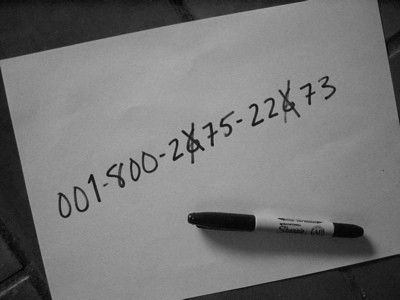

The French cling to an archaic system of naming numbers that can lead to serious confusion. You're fine until you get up into the seventies. Instead of inventing a word for seventy, and then giving the subsequent values names like seventy-one and seventy-two, the French call them sixty-eleven, sixty-twelve, and so on. Anyone who's ever taken down a phone number spoken in French can tell you this is a pain in the ass, since you write a six when you hear "soixante" and then cross it out when the number turns out to be "soixante-dix-sept," meaning sixty-ten-seven, or sixty-seventeen, or what those who value efficiency over tradition would call seventy-seven. You run into the same problems with the nineties, but even worse: ninety-eight is "quatre-vingt-dix-huit," meaning four-twenty-ten-eight. Roman numerals start to look like a better option. (Dictating IP addresses can be loads of fun in French, I discovered recently.) Naturally, native speakers of French are accustomed to this problem and no doubt rarely fall into this trap, but Ishihara does have a point. A language that aspires to become "international" should facilitate communication, not inhibit it.

Not all francophones have stuck mindlessly to this confusing system. The Belgians happily call seventy "septante" and ninety "nonante," and for embracing this simple solution they earn the endless derision of the French. As my wife says, the French would sooner cut off their legs than admit the Belgians are right, so don't expect a change anytime soon. (The Belgians also refused to go along with France's decision to eliminate "lunch" and start calling it "breakfast" just because Louis XIV liked to sleep late. They also make better French fries, but that's a topic for another post.) Whether this numbers foible is cause for the language's "failure" and whether French has failed at all as an international language are both debatable points. Whether that debate should take place in a courtroom is not debatable--let's hope a Japanese judge sees the absurdity behind this lawsuit and puts this issue back where it belongs, in the cafes.

Ishihara

Actually, the "franca" in the phrase lingua franca means Europeans in general, not the French (medieval Arabs referred to all Europeans as "Franks," and the Franks spoke German, anyway). The "Frankish language" to which the phrase refers was a sort of pidgin spoken by traders in Mediterranean ports, more Italian than French, and borrowing from Greek, Arabic, and Spanish as well. It fell out of use in the nineteenth century, though bits and pieces made their way into Polari, a mid-twentieth-century gay slang (those macho dockworkers ... who would've thought?). Today the term lingua franca more commonly refers to a language used to facilitate communication among speakers of different languages, as at the U.N. or the E.U.

French remains the most widely used common language of the U.N., but since the accession of ten new nations into the E.U. last year, English has superseded French in the hallways of Brussels. Technically, the E.U. has no official language, and all meetings, proposals, drafts, minutes, etc. must be interpreted and translated into all of the twenty currently recognized official E.U. languages, including Maltese, at a cost of half a billion euros per year. There have been proposals to streamline communications by adopting an official, "working" language, but that might offend the Maltese, so we can expect bureaucratic inefficiency to persist.

Calling French a "failed" international language is extreme, or at least premature. Despite the rise of English, French is undoubtedly the language that diplomats from most of Africa and much of southeast Asia and the middle east use when conversing with Europeans. It's still in U.S. passports alongside English, though it has been demoted somewhat by the recent addition of Spanish. To see true failure as an international language, look at Esperanto. Incredibly, the U.N. persists in wasting money on what never should have been more than an award-winning science-fair project. Esperanto turned out to be more of an exercise in creating a new dead language--another linguistic cause for fanatics to desperately attempt to keep afloat through newsletters, vanity-press publishing, and hotel conferences. Dockworkers and circus performers in Marseille, Tripoli, and Genoa proved better at creating an international language than the United Nations. Perhaps we should create a special seat on the Security Council for them, or put them in charge of peacekeeping operations.

So what exactly is Ishihara's beef with the most romantic of the Romance languages? Well, his second point is better reasoned than the first: You just can't count on the French. Oops, I mean you can't count in French. Not clearly, anyway.

Arrgh.

The French cling to an archaic system of naming numbers that can lead to serious confusion. You're fine until you get up into the seventies. Instead of inventing a word for seventy, and then giving the subsequent values names like seventy-one and seventy-two, the French call them sixty-eleven, sixty-twelve, and so on. Anyone who's ever taken down a phone number spoken in French can tell you this is a pain in the ass, since you write a six when you hear "soixante" and then cross it out when the number turns out to be "soixante-dix-sept," meaning sixty-ten-seven, or sixty-seventeen, or what those who value efficiency over tradition would call seventy-seven. You run into the same problems with the nineties, but even worse: ninety-eight is "quatre-vingt-dix-huit," meaning four-twenty-ten-eight. Roman numerals start to look like a better option. (Dictating IP addresses can be loads of fun in French, I discovered recently.) Naturally, native speakers of French are accustomed to this problem and no doubt rarely fall into this trap, but Ishihara does have a point. A language that aspires to become "international" should facilitate communication, not inhibit it.

Not all francophones have stuck mindlessly to this confusing system. The Belgians happily call seventy "septante" and ninety "nonante," and for embracing this simple solution they earn the endless derision of the French. As my wife says, the French would sooner cut off their legs than admit the Belgians are right, so don't expect a change anytime soon. (The Belgians also refused to go along with France's decision to eliminate "lunch" and start calling it "breakfast" just because Louis XIV liked to sleep late. They also make better French fries, but that's a topic for another post.) Whether this numbers foible is cause for the language's "failure" and whether French has failed at all as an international language are both debatable points. Whether that debate should take place in a courtroom is not debatable--let's hope a Japanese judge sees the absurdity behind this lawsuit and puts this issue back where it belongs, in the cafes.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home